7:49

“Who wants to build a knee?”

This was the question posed by sophomore Trang Duong to the engineers present at the Brown University buildathon in March 2016 — an annual event where builders and designers come together and make some creative, funky, and (sometimes) useful things. While many students attend the buildathon for the joys of learning, Trang was there for a much more mission-driven purpose. As the founder and CEO of Penta Prosthetics, a non-profit organization dedicated to redistributing lightly used prosthetic devices to amputees in Vietnam, her previous efforts were exclusively focused on fundraising.

But money alone is not enough to tackle the huge amputation problem present throughout the developing world. It’s not just an epidemic due to war and unexploded landmines left behind, but also due to inadequate medical care to save limbs lost to infections and accidents. The gap in the supply of donated used prosthetic limbs and the demand for them in Vietnam led Trang to explore ways to inexpensively produce new ones. What better place to look than a buildathon?

One of my peers, Alexander Lo, participated in this event and made an instant connection with Trang’s mission. She liked his enthusiasm and unique perspective on mechanical orthopedic design and asked him to gather a team to help tackle this project. Alex, his twin brother Matt (UX/ Support intern), and I (who later became the co-founders of Koi Prosthetics) put together a team of undergraduate students from Brown and the nearby Rhode Island School of Design. Cumulatively, we had backgrounds in biomedical engineering, mechanical engineering, and industrial design.

Our team collaborated with Trang in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam to oversee the distribution of the prosthetic devices she had collected. Our goal in Vietnam was to conduct user research, and if we had a viable product, potentially conduct physical testing. Through a combination of inexperience, enthusiasm and hubris, we had an ambitious goal to build a testable prototype within four months. We wanted to capitalize on a potentially once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to help people needlessly suffering because of their place of birth.

Our First Design Challenge

The initial design challenge was quite difficult. Every answer we found in our research produced more unanswered questions. But steadily, we forged ahead with rapid prototyping techniques. As our designs progressed, we realized our need for more powerful design tools. Back-of-the-napkin sketches led to low-fidelity prototyping which ultimately led to the need for a CAD system. Candidly, we assumed we would be using SOLIDWORKS because that was the license our school had and what we had been taught in our curriculum. We’d heard of some of the nightmares of product data management, but were ready to face those turbulent waters together.

However, as the summer approached, we foresaw a looming issue: none of us were going to be in the same place, but we all needed to collaborate on CAD and mechanical analysis software. Serendipitously, one of the members of our team, Isaku Kamada, was previously an intern at Onshape. None of us had heard of Onshape, but the concept of a cloud-based design platform was enough to sell us on the idea almost instantly.

While our team had some fluency in 3D geometric modeling, we were not professional CADers by any means and had a lot of room to grow in the space. I think this experience benchmark turned out to be a sweet spot; knowing how to use CAD, but not having any strong affiliations to any one brand made for a smooth transition into Onshape. The platform offered an intuitive interface and an easy means of collaboration while tracking changes. We not only found the functionalities that we expected, but also some that we didn’t even know we needed — things like versions, branches, and Linked Documents all became vital tools as we iterated remotely.

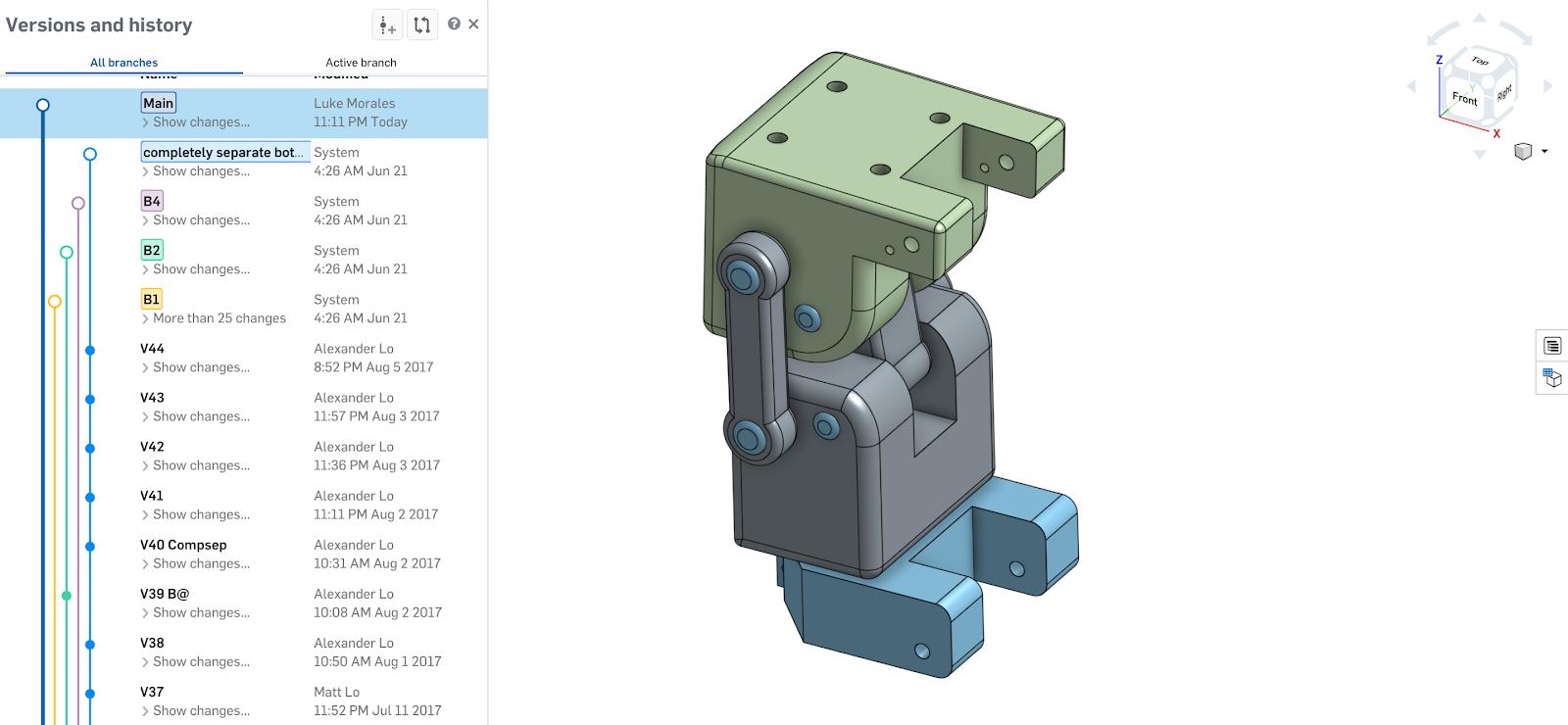

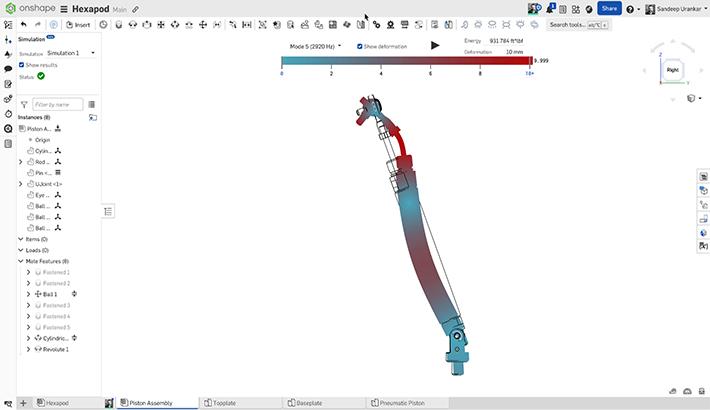

Using branching and Onshape’s built-in version control to create our first prosthetic knee designs.

Bringing Our Mechanical Knee to Vietnam

Something we didn’t build into our timeline was wiggle room — we only had one shot to get the design and a testable prototype right if we wanted to stay on track. Onshape’s unique cloud database architecture spared us the headache of stepping on each other’s toes and allowed us to CAD on the fly without having strict dimensioning rules set up beforehand. This streamlined our workflow and helped to mitigate errors. Our designs grew in complexity, and many versions and branches later, we finished our prototype just in time for Vietnam. It was far from perfect, but we were proud of it.

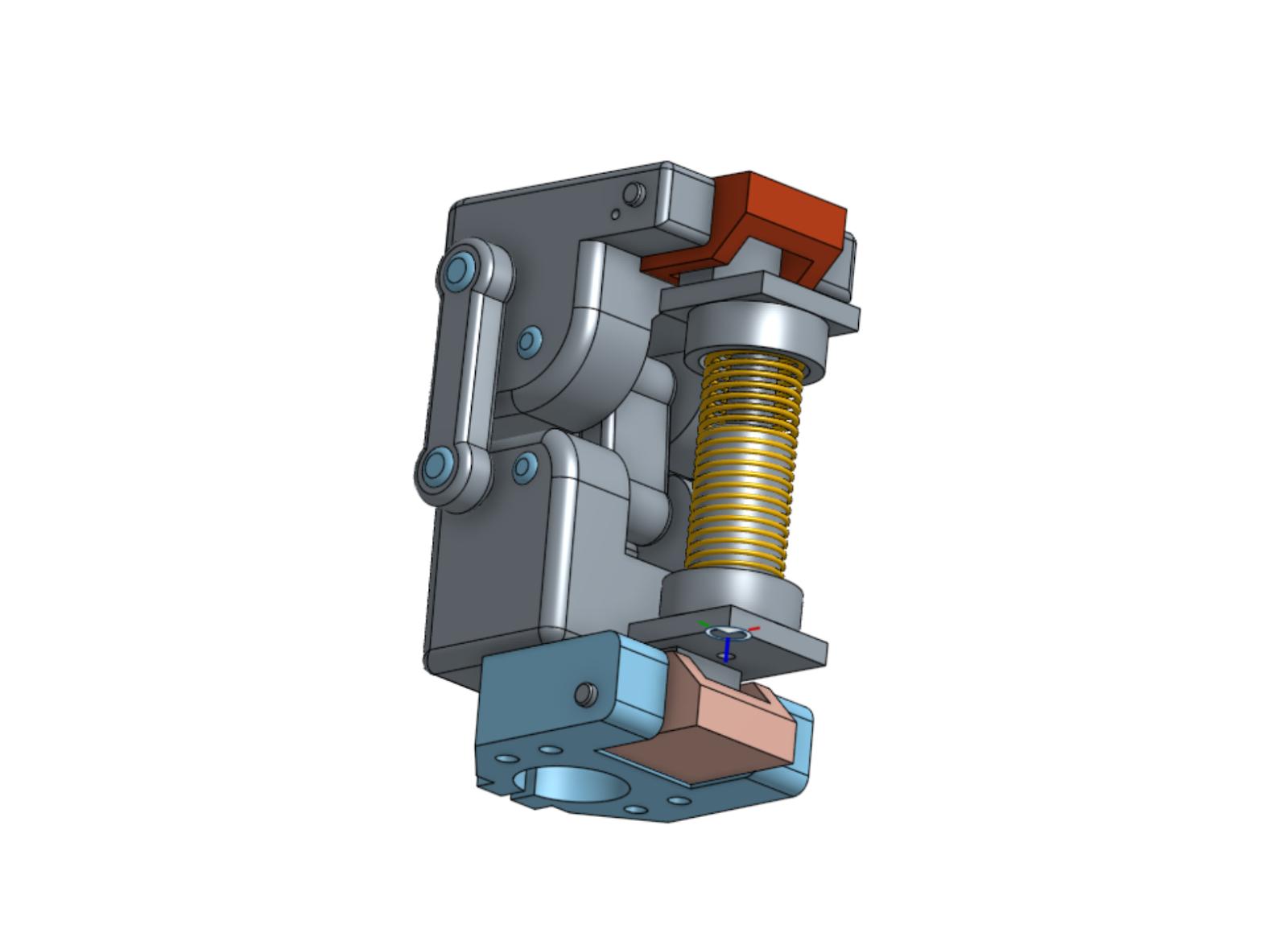

Our first prosthetic knee prototype designed in Onshape.

Our trip to Ho Chi Minh City was a genuinely eye-opening experience. We had the opportunity to observe firsthand how a developing country handles various aspects of their infrastructure. The culture shock was pretty substantial for all of us over the first few days. The streets were filled with an almost unfathomable amount of motorbikes with little to no obedience of traffic laws. Crossing the street required “walking with conviction and purpose” as Trang instructed us, to allow for oncoming bikers to predict your path and swerve around you. The humidity during monsoon season was oppressive and the crowded streets didn’t help. Yet the city had a charm to it, filled with good food, great coffee, and a comfortable feeling of anonymity (that comes with the bustle of a crowded city) that made the heat and traffic much more bearable.

Our first hospital visits with Trang were particularly jarring. Different departments of the hospital were siloed from one another, the hallways were dimly lit, examination rooms provided little privacy, and the conditions of the laboratories used for making prostheses were a far cry from the level of medical care we were accustomed to. Though lacking in resources, the urgency in the beat the doctors marched to seemingly held the systems together. Doctors and nurses made do with what they had, but they were fighting a losing battle. The system itself was slammed, with the supply of prosthetics consistently falling short of the demand.

Unfortunately, we discovered some complications with our initial design through feedback from doctors and amputees, and thus we were unable to conduct physical testing. We were pretty bummed, but knew our direction with future iterations of our design. With two weeks left in Vietnam, we spent our time observing and participating in the testing and fitting of other prosthetic devices. We learned a lot through our immersion in these testing environments, and were able to discern some of the flaws in both existing designs and the system itself.

Our team collaborated with prosthetic clinics to receive feedback on our prototype and existing products.

The most important part of that trip wasn’t necessarily the work we did, nor the data we collected, but rather the feelings that patient interactions instilled in our team. There’s a stark difference between reading numbers on a computer screen and seeing firsthand what those numbers actually represent. Those data points are people with their own lives and struggles living in a society without the infrastructure to support them.

It might seem trite to an outsider, but I vividly remember feeling a pivot in the way we viewed this project. Just knowing that something we were attempting to create could eventually be a pragmatic solution infused humanity into our project. Our goal morphed into something bigger: If we could improve the quality of life for even one person by the time we put down our pencils for good, then this whole endeavor would be a win.

Upon returning to the US, we all felt that what began as a contracted project had evolved into something more than a one-time job. After talking with Trang, we came to the conclusion that we wanted to continue this work as our own start-up company, Koi Prosthetics. We chose to name the venture after the koi fish because it is a recurring symbol of perseverance in the Asian countries we were initially working in. Our goal is to help amputees regain their autonomy and persevere through their new challenges.

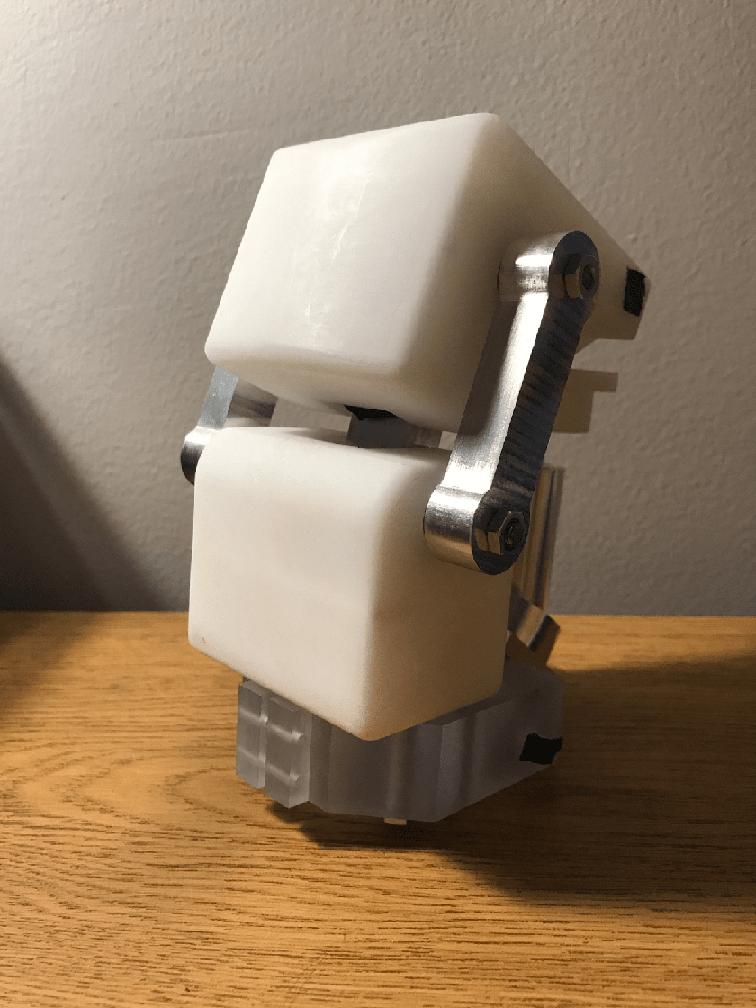

Koi Prosthetics co-founders Luke Morales and Matthew Lo machining usable prosthetic socket prototypes at the Brown University Design Workshop.

Over the past two years, our startup has grown substantially to incorporate a larger team, multiple lines of prosthetic products, and a larger network of advisors. We have since expanded our focus beyond the knee to a suite of prosthetic devices that together comprise an entire low-cost prosthetic leg.

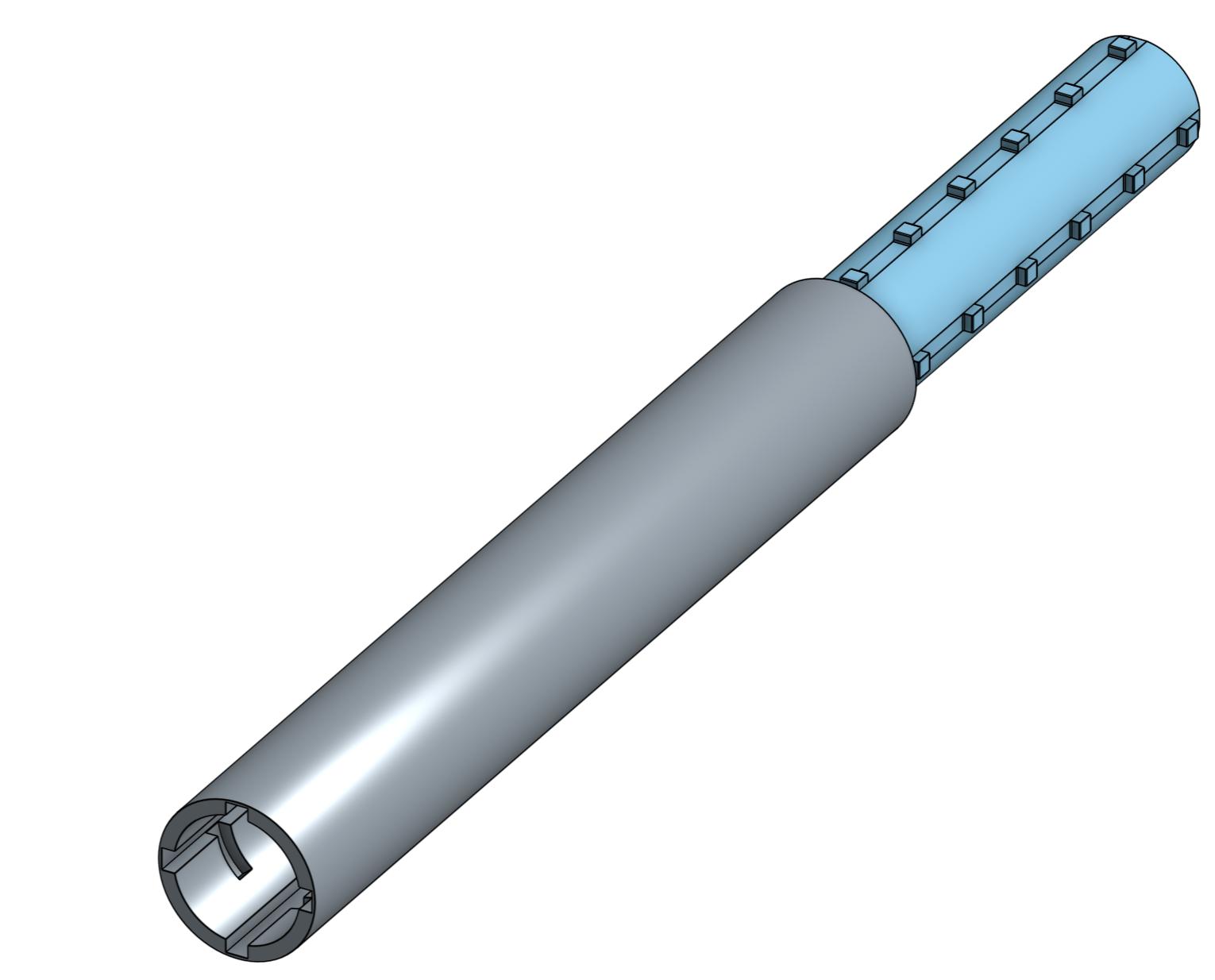

Designs and prototypes of our new prosthetic knee, universal transfemoral socket and adjustable pylon.

While all of the initial founding members of Koi Prosthetics have graduated from Brown, many (including myself) are still actively working on the designs. Onshape has proven to be invaluable for keeping our dispersed team on the same page whenever there are design improvements or new challenges. Anyone can look at the edit history and see who did what and when — or even revert to an earlier version of the design and start a new branch to explore alternative ideas.

Looking back on our Vietnam experience, I believe that much of our early design success stemmed from Onshape’s ease of collaboration. And I expect Onshape to continue to play a critical role in Koi Prosthetics’ mission to deliver a better quality of life to amputees worldwide.

Latest Content

- Case Study

- Automotive & Transportation

Zero Crashes, Limitless Collaboration, One Connected Workflow With Cloud-Native Onshape

12.04.2025 learn more

- Blog

- Becoming an Expert

- Assemblies

- Simulation

Mastering Kinematics: A Deeper Dive into Onshape Assemblies, Mates, and Simulation

12.11.2025 learn more

- Blog

- Evaluating Onshape

- Learning Center

AI in CAD: How Onshape Makes Intelligence Part of Your Daily Workflow

12.10.2025 learn more

- Blog

- Evaluating Onshape

- Assemblies

- Drawings

- Features

- Parts

- Sketches

- Branching & Merging

- Release Management

- Documents

- Collaboration

Onshape Explained: 17 Features That Define Cloud-Native CAD

12.05.2025 learn more